Text: Emma Mether and Johanna Sumuvuori

Report on journalist workshop: Interpreting Crisis: Reporting on Migration, Asylum Seekers and the Syrian Conflict. Monday 24 October 2016, 11 am – 2 pm, EFJ, Brussels

On 24 October the Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux, the Finnish Institute in London, Felm, and the Media Diversity Institute organised a workshop at the European Federation of Journalists headquarters in Brussels. Two reports functioned as background for the workshop: The Representation of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Newspapers (January 2016), carried out by the Finnish Institute in London and the Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux, and Syria in Global Media, commissioned by Felm during 2015-2016.

The aim of the workshop was to discuss the challenges journalists face when reporting on migration, asylum seekers and conflict, and to raise a dialogue on the preconditions and effects of journalism and on the challenges of reporting migration and the so called ‘refugee crisis’ in the press. The question at the centre of the workshop was: What are the ways to represent refugees and asylum seekers, and how is it possible to do versatile, ethical journalism on Syria?

Summary of the workshop discussion – key questions

Partiality

One of the crucial problems journalists face when reporting on conflict, is the difficulty to remain objective while at the same time not taking security risks. To be a reporter in the middle of a conflict area almost unequivocally means working with one side of the conflict. Freelance reporters not taking sides are often not trusted by either side, which makes it challenging to gain the trust of sources.

Additionally, media owners tend to buy stories from freelancers instead of sending in their own reporters, which puts freelance journalists in further hazard and uncertainty. Ironically, journalists working for large media companies are treated with more respect by representatives of all sides of a conflict, while freelance journalists are more vulnerable. How do we address these issues of safety and reliability?

“European crisis”

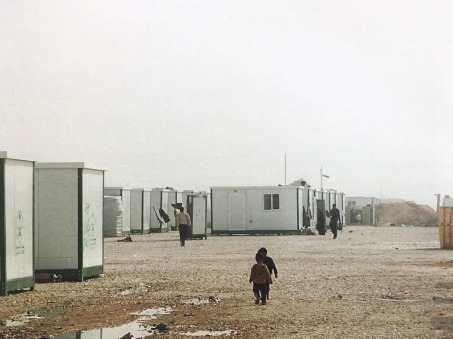

In terms of media coverage on the Syrian war, by far most of it is given to terrorism and conflict, the subjects being mostly males, as the Felm study suggests. Humanitarian aid and peace negotiations are given a considerably smaller amount of focus, as is the case with reports on women and children. This of course does not reflect reality. Regarding newspaper language, the Syrian conflict is often reported from a Eurocentric perspective, with the ‘crisis’ being one that faces Europe. The ‘refugee crisis’ is seen as a threat to a harmonious European society, similar in effect to the economic crisis. As such, a humanitarian point of view of the afflicted society is often absent, making the people affected stand out as a faceless mass, incomparable as people to the conflict-free societies of media consumers. The influence of the media on public opinion and world view is notable, which of course highlights the responsibility of journalists. What steps do we need to take to make media coverage and language more humane and closer to reality?

Syrian journalists are rarely consulted or hired when reporting on the Syrian war, further confirming the Euro- or West-centric point of view. Local reporters are automatically considered unreliable due to a preconception of them working for the propaganda of one of the conflicting sides. However, local reporters have the advantage of better understanding the culture and the experiences of the people affected. How do we create a bond with local reporters and include them in the reporting of their country?

Ethicality in the media has changed with the reports on Syria. It seems that traditional rules of ethics and the idea of moral conduct have been dropped, reflecting a new openness or directness also visible in the now prevalent hate speech on social media. How do we secure that ethicality standards are followed?

Proposed solutions by the workshop

On the basis of the workshop discussion, a few main suggestions for future focus stood out.

Firstly, solidarity between journalists is crucial for professional cooperation and mutual understanding. Solidarity would mean safety protection and more openness, which in turn would allow for better coverage. It would also lower the threshold of working together with local reporters. Creating large-scale solidarity among journalists requires cooperation with non-political organisations.

Secondly, editorial processes should focus more vigorously on the ethical point of view. Ethical guidelines for journalism have been produced in abundance and are available. The issue is rather that, as the two studies show, reporting often does not follow these guidelines. A revision process is thus needed that would make the work visible and open for debate. This type of permanent and public monitoring would lead to a greater commitment to follow guidelines. The aim is a model for a new crisis journalism.

Finally, media education and media literacy should become a focus in education. This is something that needs to be relied to state-level decision makers in order to implement it in school curriculums, both at elementary and university level education. Although it is our aim, we cannot only trust that all reporters can be properly schooled in ethicality and that a discipline-wide solidarity will be rapidly built, but we must also take responsibility of teaching people how to read the media as it is now.

Emma Mether, Intern, Finnish Cultural Institute for the Benelux

Johanna Sumuvuori, Head of Programme (Society), The Finnish Institute in London